Silent specters, JET, Berlin, 2007

The unsung apparitions of this exhibition are those of history and the subject’s processes of becoming. Yet they are only playing dead, for such phantoms haunt us ceaselessly. Because attempts to contact them commonly fail, Flo Maak instead works in the hope that they might be encountered through images. Ideally, this might mean by determining the place from which they observe us.

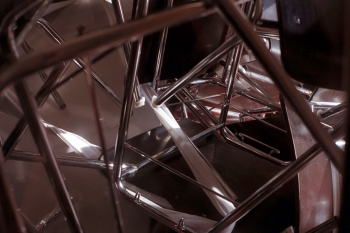

Illuminated with magical light, a photograph of jammed together chairs that have been bound together with strips of fabric, like most of Flo Maak’s works, documents a found situation. In Maak’s work, incidental everyday encounters—usually fixed in photographs and expanded by spatial arrangements—render the loss of the past visible while evoking the possibility of another, liberated reality. In The barricading of the emergency exits with chairs jammed together prevents the continued use of the elevators on account of safety regulations the chairs, bereft of their initial function, appear to be standing by for some alternate purpose. Corresponding to breakdowns in everyday communication, a necessity for interruption is here posited as an essential step towards a good life, while at the same time such situations foreground ambivalence and a vague feeling of menace.

A picture of a brightly lit toilet cubicle is the only photograph in the exhibition that has been staged. It is part of a larger group of works that investigate public toilets. Its title The door closes, the light stays on underlines the fact that particular sites function as an enclave for private needs within the public realm. It also points to the normative authority of such a site for the purposes of gender segregation within social contexts. The light in the photograph blows out into pure white, bleaching the site of its intended function and raising instead the possibility of its conversion for other more sensuous purposes.

While searching for holiday accommodation they chance upon a house on a hill near Pompeii. They enjoy the view of the sea and converse about dead revolutionaries and coming revolutions. It turns out that the late owner of the villa was a communist, art historian and formerly a prominent lecturer on proletarian photography. The previous sentences are the title of an installation constituted by a photograph, an object and a film. The photograph was casually taken in a holiday home in southern Italy. It was only later that Flo Maak learned of the story of its late owner, Dr. Richard Hiepe—an art historian and publisher of the Marxist magazine “Tendenzen” (Tendencies). Because of his membership of Germany’s Communist party, Hiepe was denied a professorship in Germany. While image and object present the melancholic residue of this lost story, the film takes the exhibited photograph as its subject and embarks on a science-fiction like trip with it into the past future.

What remains in the end is loss. In the centre of the exhibition a small-scale picture in a black frame is placed on the floor. It is an image of a bouquet of flowers emerging from a shadow with two daffodils bourgeoning from its faded centre. According to ancient mythology such flowers bloomed after the death of the beautiful youth Narcissus, who, besotted by his own reflection in water, drowned while trying to embrace himself. The melancholic traces that each individual carries within as an index of their own development as a subject seems in Narcissus to have attained an uncanny degree of condensation.