Doing nothing like a beast at Bielefelder Kunstverein, 2009

»The limitation of sensory perception to seeing makes the producer of images into a voyeur.«1

The Bielefelder Kunstverein is the first institution to mount a solo exhibition by the Frankfurt artist, Flo Maak (born in Fulda in 1980). In his photographs, photo-collages, objects, and his video and sound works, he investigates the conditions of situation, image and exhibition. To this end, this artists resorts to found image motifs as well as to those he stages himself.

This artist’s works are predominantly photographic and result from engaging intensively with the relationship of private and public spaces. This becomes obvious through earlier groups of works, which focus on image motifs like public conveniences, pedestrian underpasses, interiors, utilitarian objects and plants. In the process, this photographer with his keen eye for situations plays a decisive role, as does, however, the principle of chance. And for a good while now, Flo Maak has been equally working with collage as a creative vehicle: he combines and arranges his own and found image motifs, plays with the size-relations, and constructs his own scenarios. These in turn serve as the pictorial background for collages or translate collages into spatial structures. In the sense of extended photography, alongside and in conjunction with photographs independent objects and vehicles for images arise, which the artist often brings together into narrative spatial constructs. The atmosphere surrounding his work is permeated by its particular underlying melancholic mood, which can be read both pictorially and formally.

In this sense, the exhibition, »Nichts tun wie ein Biest« (Engl.: Doing Nothing, like a Beast«) does not frame itself so much as a collection of individual exhibits, but rather more as a dialogue of photographs, photo-collages, objects and one sound piece. What puts a bracket around its content is the complex relationship between humans and animals. In shaping this, the artist has quite consciously picked out individual aspects like the question about the division between humans and animals, like spectators’ pleasure as staged in concrete locations, or the analysis of structured environments, such as, for instance, nests, caves, refuges, houses, apartments etc.

In his current images, photographic portraits of wild animals dominate and conform to the usual depictions of animals only partially. His pictorial translating of animals in zoos or wildlife parks ranges from documentary snapshots to the digitally-manipulated group of works entitled »shelter« (2009), where animal photos are combined with interior environments. Spatially, the exhibition’s structure derives from three coloured objects featuring steps and stages. Spectators use them and so become part of the staging. The exhibition is a game with a staged voyeurism, which governs media and event culture and, with that, our everyday life.

The encounter between humans and animals is marked by mutual lines of sight: looking and being looked at. We can observe such situations in everyday life, for example, in the relationship between pets and their owners, and people stage them spatially in quite concrete locations. Among these places figure zoos, wildlife parks and entities like circuses and the like. Sabine Nessel maintains that zoos and cinemas can also be designated modern spectatorial entities, which have helped to determine the perceptual history of modernity. In one respect they correspond in as far as they give a mass audience access to »living images« or »moving pictures« respectively.2

To this end, the works Flo Maak has produced for the exhibition seek and create particular answers in pictorial form: »Ohne Titel (Kopenhagen)« (Untitled [Copenhagen]), 2009, shows a polar bear diving with its body dissolving into a diffuse mark in the water. Here, the animal withdraws for a moment from the zoo visitor’s sight. »Ohne Titel (New York)« (Untitled, [New York]), 2009, depicts the situation of staged voyeurism and, per se, the separation of humans from animals. What we can see is a gorilla walking on all fours behind a glass screen and being observed by a zoo visitor seen from behind. The words of art historian John Berger are appropriate to this pictorial motif: »He does not reserve a special look for man. By no other species except man will the animal’s look be recognised as familiar. Other animals are held by the look. Man becomes aware of himself returning the look.« 3

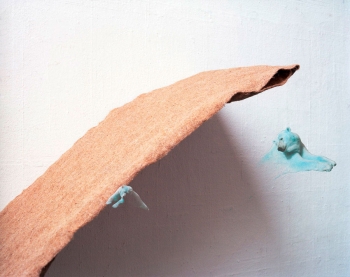

The motif of animals re-surfaces in the group of photo-collage works, »shelter« (2009), in an altered fashion. The point of departure consists of shots of animals from zoos or wildlife parks, which are combined with three-dimensional, seemingly almost sculptural interior scenarios, in which the concept of virtuality4 is investigated and the human/animal relationship to the structured environment is illuminated. What the artist understands by virtuality is a space of possibilities, which is actually not purely fictive, but simulates reality, presents it in isolation and carries within itself an assertion of the event. The space of possibilities was achieved by means of staged photography. In that process, simple resources generated a sort of landscape or housing, which points to the title of this series of works (shelter in English, as a hidey-hole, a refuge). In this scenario, Flo Maak enlists digital image-processing to produce collages of individual animals or of pairs of animals, which maintain a pose typical of their species, but are presented as radically miniaturised or mildly alienated. In this way, the pictures swarm with: polar bears, sloths, herons, loris and zebras. On a closer look, we can make out a carefully arranged environment, actually a matter of a surrogate, as a harmonious unity with the animals integrated into it, and this makes the absence of humanity all the more obvious. By contrast, the sound work, »Auf die Bühne der Natur« (On Nature’s Stage) (2009) stands for a reversed variant of the »shelter« photographs: what we can hear are recorded ambient noises (park, apartment), humans imitating animal noises and fragments of text, which recount human/animal encounters. Here the environment is created in sound, and the actors are part of our fictions.

To hear this audio work, we have to climb onto one of the podiums, which are scattered around the exhibition and are reminiscent of objects incorporating steps and stages. From top to bottom, the steps are set out in graduated colours in opposition to the spectrum of natural light. It is only from the bird’s eye view that we can perceive the colour concept in totality. The artist created these spatial objects as an invitation and an offer, so that the spectators become part of the staging. We find ourselves in a dual role: object (as something looked at) and subject (as spectator) in equal measure. What is significant in all this is our own experience of the shift in perspective, of being on display and of becoming conscious of ourselves. Here, the photography becomes a voyeuristic game, which consistently includes a multitude of ways of seeing and in that takes up those it is observing into the game. Yet amidst this game of staged voyeurism, we should not forget its art. The (public) zoo emerged around about the same time as the art museum in the 19th century, and so we can find many a parallel between what zoo visitors get to see and what visitors’ experience at this exhibition. What remains is human’s unmitigated scopophilia, reflections on animal-and-non-animal existence or, to close with the words of Friedrich Nietzsche: »Civilisation is the enforced animal-taming of humans.«

Text: Cynthia Krell

English translation: Anja Welle, Stan Jones

1. Rolf Sachsse, Bild – Medium – Wirklichkeit. Funktionsbestimmungen der Fotografie, in: Fotovision. Projekt Fotografie nach 150 Jahren, Hannover 1988, p. 46, own translation.

2.Cf.: Die Tiere sind da! Medialität und Präsenz in Zoo und Kino, in: Doris Kern, Sabine Nessel (ed.): Unerhörte Erfahrung. Texte zum Kino, Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt 2008, pp. 216-227.

3. John Berger, Why look at Animals?, in: John Berger. Selected Essays, G Dyer (ed.), London 2001, p. 260.

4. Aristotle already provides a basic definition, which determines the wider discourse on virtuality right up to the current discussion in philosophy. The articulation of the virtual appears as a manifestation of an event.